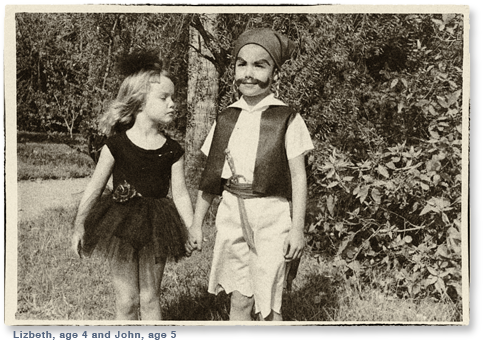

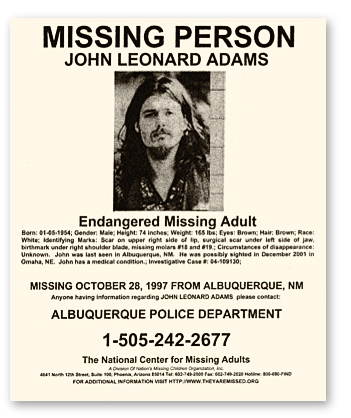

My family searched for John, in one way or another, for most of his adult life. When John periodically disappeared from their home my parents filed missing person reports (MPR). Often, John would soon come into contact with law enforcement (for jaywalking, for example) and the MPR would have to be withdrawn. By the time I took over the search from my parents, the criteria for filing an MPR had become much more stringent, and it required nine full months of repeated effort before I was finally able to find a person, in New Mexico, who agreed to take the report.

The importance of filing an MPR is that the person’s information and status is then entered into national databases such as NCIC (National Crime Information Center) and NCMA (now merged with Let’s Bring Them Home). As a consequence, it becomes much easier to cross-reference national datasets to see if they have been arrested, or information exists that they have died. The social security death index provides information on deceased people, but only if they had identification on them when they died, or there was some way to link them to their correct social security number. This is not always the case with mentally ill and transient people.

In John’s case, nothing turned up when the national databases were checked. So, I began to apply a brute force approach. I called prisons and hospitals, county coroners, homeless shelters, and other agencies throughout the west, southwest, and Midwest. I did everything I could think of to uncover information. I did this for six years. It felt like the most random, hopeless, ridiculous undertaking, and yet the most important thing I had to do in my life.

Most of the time, bureaucrats invoked privacy and confidentiality laws and refused to give me information. Finally, a retired attorney in the Santa Cruz police department who has dedicated his retirement to helping people find their lost loved ones told me to try once again to file an MPR with my local police, an agency that had refused my earlier requests. This time, for whatever reason, they agreed to take the report, there was a hit, and a police officer came to my door to tell me that my brother was dead.

Listen as Lizbeth discusses the grueling search for her long-lost brother:

Print Media

A vanished brother, veils of secrecy and the sister who would not give up (March 17, 2012, Seattle Times)

Finally a chance to mourn (March 22, 2011, Seattle Times)

John Leonard Adams: obituary (March 2, 2011, Seattle Times)

A vanished brother, veils of secrecy and the sister who would not give up (March 17, 2012, Seattle Times)

Finally a chance to mourn (March 22, 2011, Seattle Times)

John Leonard Adams: obituary (March 2, 2011, Seattle Times)

As Lizbeth's parents searched for John, they ran into one dead end after another. When Lizbeth took over the search from her parents, one of the first things she did was hire Winquist Investigators in Kenmore, Washington. Rose Winquist and Bob Stockkham were of tremendous help in her search. If you, too, are looking for a loved one, there are a number of government and private agencies that can assist you.

Where do you start?

Where do you start?

- Make a report to law enforcement. Try to get an advocate within law enforcement that will take your concerns to heart.

- Check court records in the area where the person last lived. This includes municipal, county, state and federal courts. This should cover anything from a parking ticket, civil or criminal actions. Courts also have name changes. Most states have free databases like Washington (see below).

- Check the Social Security Death Index

- Contact Social Security regarding your search for a missing loved one. The person making the inquiries should be a next of kin. They will send a letter to the person's last known address if they are receiving benefits.

- Call mental health facilities

- Get in touch with the Salvation Army and local homeless shelters

- Post and distribute flyers

Free searchable databases in Washington include:

- Ibloom (Washington State employees)

- The Confidential Resource

- Washington State Court Research

- Washington Voters Search

- SSN Death Index Search

- Business and Professional Licensing

- Physician-Nurses-CNA